Ujna Mărioara

85 years old, born in 1937

I don’t know who takes the time to listen to these elderly children anymore. I didn’t want to intervene too much in this interview, to extract the most valuable bits. I feel overwhelmed by her years, by her joys as well as her sorrows. Get yourself an elder if you don’t already have one.

I come from a family of peasants, of carpenters. My father built a small loom which was in the museum for a while, but who knew how much it was worth, it was sold, I kept a photography of it.

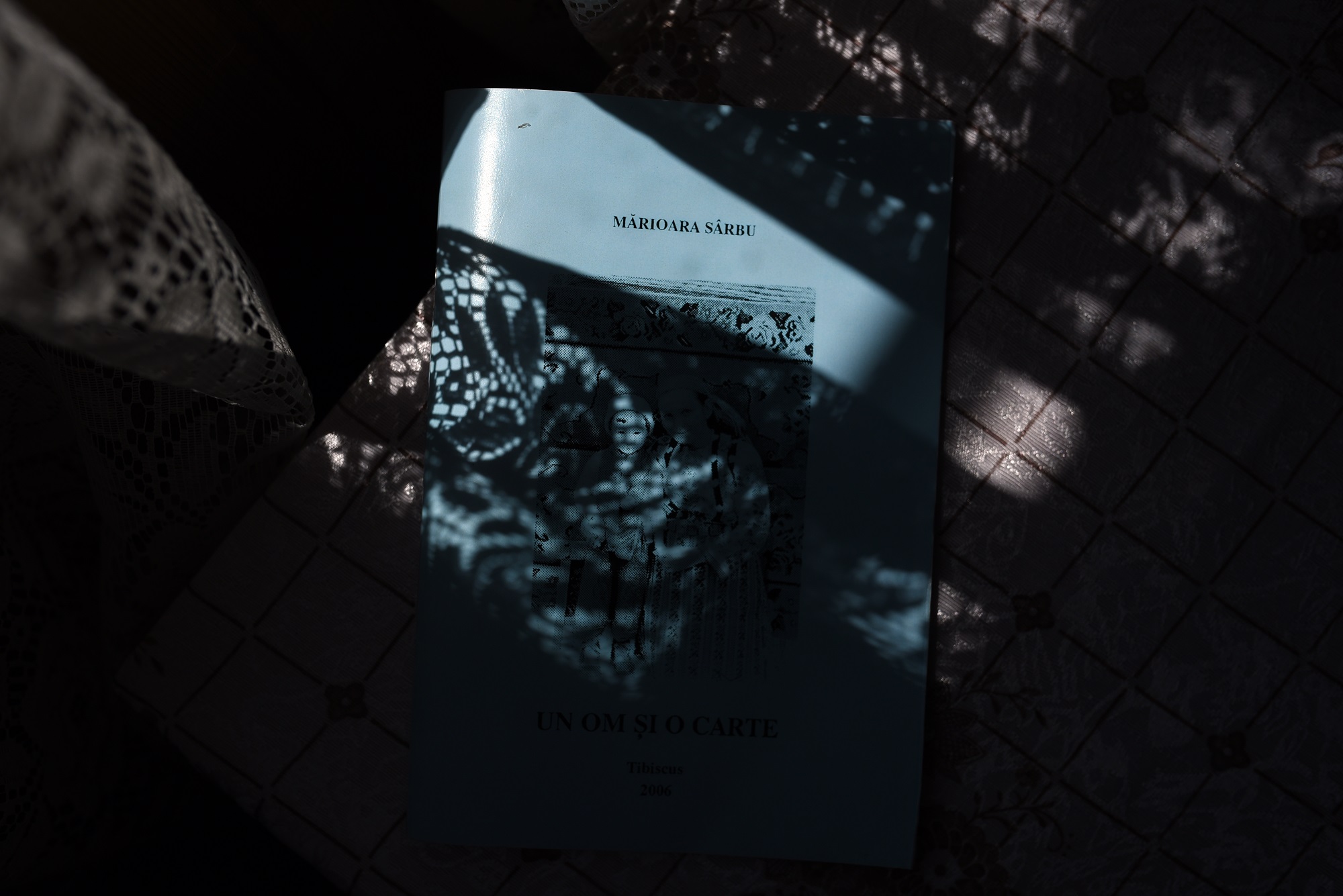

If the parent knew how to draw a line, so did the child. It depended a lot on the parent. I wanted to go to school, I yearned for school all my life, but my parents didn’t have the money. Here, the ones who had red party books went to school, no matter the grades. My heart still aches with regret that I didn’t take Romanian classes after my husband died. I was sick, paralyzed, I had to sit still. I was 64 years old. My husband and I got sick one day, he fell into a coma, I became paralyzed. After that, I wrote a memoir, a book. Ujna Maria came dressed in black, according to tradition, wearing a headscarf. She sat quietly in her chair with her purse on her lap, and when we reached this moment in the story, she opened the zipper and pulled out her book. Not a moment sooner, not a moment later. Strategy.

A PERSON AND A BOOK. The prose is in Romanian, the poetry in dialect. I have a character, Vărzăvia, in whose mouth I put everything I don’t like and many other things I’ve written here.

Have you always wanted to write?

I have written poems meant to be shouted at dances, wise words, stories in dialect, everything related to Uzdin and the people here. Mrs. Otilia in Timișoara has many notebooks of mine, I’ve given them away, written and forgotten.

Did you give away the originals? Are they now wandering around the world?

Yes.

Do you still have notebooks at home?

Yes, I still have some.

Are you still writing?

I can’t see anymore because I had surgery on both eyes. But I really miss it. I really wanted to go to a cousin of mine in Galați, to sit in a corner and listen to people speak Romanian. And God made it so that I got my wish.

What do you remember doing here as a young girl?

What can I say, I was just another pebble in the world’s shoe. I didn’t leave Uzdin, I was a peasant, I went to the field, I did everything a peasant did. Numa, my husband, was a football player. I never once told him why do you stay longer than you have to, he didn’t once tell me why do you write since you are a peasant. There was a harmony between us when it came to passions. And then there was my mother-in-law, I had a great mother-in-law. The world can say whatever it wants, but my mother-in-law sided more with me and scolded her boy for not behaving.

We shared a house, and at one point my mother-in-law didn’t know what I was working on in my room. My father-in-law went to lie down in his room and she came to see what I was doing. As it happens, I had just written a poem about a good classmate of mine, Ana Petrovici, and she wanted to know what I had written. She thought it was maybe a love letter or something, I don’t know what she was thinking. And when I read her the poem, she cried. And she said, I’ll go tell people in the village what you’re working on. She had been told by someone that I don’t do work, that I don’t know how to do things. I wasn’t interested in what people said. NO ONE could take away from me my love of the Romanian language.

How did this love of language appear? Have you always had it?

I started by reciting poems for Mr. Mezin Petru, a teacher. I was his pupil. Then I recited for Gheorghe Lifa. I used to go to all the villages to recite poems, I was a must in the program. Even now I like to recite. Then God gave me the chance to meet Mr. Ionescu Gheorghe, a teacher from Romania, who came on a short-term contract. He taught us Romanian for a year. I would have liked him to teach us for longer. From him I learned all the pins and wheels of the language. He left and then I met Mrs Otilia Hedeșan and the female teachers. She sat with me and wrote a book in which I told her about Uzdin in detail. (Otilia Hedeșan, Uzdin in Detail. The Recollections of a Prodigious Storyteller. Mărioara Sârbu)

At the hospital, the nurses used to ask me who the books on the bedside table belonged to, and I told them that they were mine, that I was the one reading. I read Anna Karenina three times. My husband, before he started drinking, would go to the library and bring me books, and on Sundays the whole world would be outside, and we would read together in our room. Each with his own book. He sold grain, watermelons. And he was very good at football, he played with passion. And he was handsome, all the girls admired him.

Did you fall in love with him? How did you meet?

We were neighbours, we went to school together. My parents told me that they didn’t have money to keep me in school and that I had to choose one of the children my age. (In Uzdin, when they say child, they automatically mean boy). And I chose the neighbor.

And did you have a good marriage?

(She hesitates, sighs) We did. With ups and downs. I have a daughter, she’s a writer and translator. I also have a granddaughter, a PhD student, she’s been working in Austria for 6 years. She also has a little boy. I know I’ll never see him again. I have a son-in-law, a German, that’s how much he values me. And sometimes I’m ashamed because I’m a peasant. I’m not afraid to say I’m a peasant. They sent me 37 photos of the baby, so I have something to keep me busy, something to look at.

I’ve got straight A children. If there was a higher grade, I’d give it to them.

A +

Where did you get your inspiration when you were writing?

I like to write about what I see around me, about people, whether they are good or bad, about customs.

Do you consider yourself a good mother? Were your parents kind and understanding to you?

My father, who was born in 1900, read a lot, and all the poems he knew, he taught them to me. I still know some of them.

By heart?

Yes.

Did you learn them?

Yes.

Do you still know any?

Mărioara, in a different voice, as if on a stage, begins to recite the poem. The joy on her face is priceless. I now feel guilty about her moments of loneliness. As I listen to her, I wonder what she’s doing.

Silly, won’t you mind your business,

Won’t you give that cat a break

If only your dad was here to see

How you’re pulling her poor tail

Mommy, I would happily stop

For I’m not enjoying this

But I am simply holding her

She’s the one provoking me

There are more, but this is the one that came to me. In our house, books were highly valued. My grandpa read the Bible. I learned from him that you shouldn’t take a dinar you find on the ground unless a bead of sweat has fallen off your face. Don’t covet something of your neighbor if you know we can’t give that to you. And my father required me to study, not necessarily to be the best in class, but I was anyway. In 6th grade my appendix burst and it was really bad. I had surgery. I’ve been cut up and down. My ulcer burst three times. EVERYTHING OLD AGE HAS, I HAVE IT.

What happened to your appendix? Where were you? At school?

At home. I was supposed to go sing a solo, At the Mirror. (the only song I still know and love from my childhood and Ujna Mărioara brings it up, but she doesn’t trust her voice anymore, she says her tongue and teeth are dull) I was on the edge of death, but I made it. (and yet she sings to us, maybe you too know the song)

Today I’ll notch the beam,

Take the mirror off its nail

Mother’s away in the village

The baby is home all alone with her longing,

And I’ve closed the door to the house

With the latch.

My father always let me recite in all the villages in the commune. He used to say, books and learning are not eaten with a spoon, they are hard earned by going to school all the time.

Have you thought about becoming an actress? Did you want to?

I was in one play. Mother, by Maxim Gorky. I was a maid and after that, other actresses “sprang up”. I thought they were “better” than me and that I should give up.

Was it you who thought that? Or did others?

Me. A very firm and determined answer

Why?

Because…

What did they have that you didn’t?

To say or not to say….

Yes, say it, because it’s still happening and it’s good to say it.

They were more to the linking of men…

Yes.

And you didn’t want to do that.

I didn’t want to… I was small in stature, skinny. What can I tell you, a scrawny girl.

But you have a mouth on you, don’t you?

Yes, and it doesn’t go away.

But did you do that role?

Yes, I played here in Uzdin. I got other small roles too. When they had no one else to ask, I would come and act the artist for a bit.

Did you also act the artist at home?

Ujna Mărioara laughs and laughs

I like to talk, why not talk, that’s what I know, but lying and liars, I can’t stand them. Tell the truth. I like to look into your eyes and tell you the truth. Dark as the truth may be, I have to recognize it. And if I’m wrong, I’m wrong.

Do you mind if I ask you more direct and personal questions?

No.

When your parents told you that you had to get married, how was it for you? How old were you?

15. I had just passed the end of secondary school exam.

Yes.

Of course I did.

Did you want to?

Two weeks I stayed locked in my room and didn’t even come out to eat with my parents. But, seeing that there was nothing I could do about it, it was around the time they bombed Belgrade and I was afraid, my sister was also at the age of marrying. I didn’t want to get married until I was 18. Even though that was my wish, nobody listened, it was what it was.

Did you think about leaving after you got married?

No, I stayed and whatever came my way, I endured. I knew that if I could bare to part with the school bench and school, I could bare everything in life.

When you look back, do you see a lot of regrets or other things? Do you see a lot of black?

I’m sorry when I see people who are dumber than me and they have more crutches. I don’t like the way kids learn these days, only interested in FB and… No! You don’t feel the same sweetness as when you say 2 x 2 is 4, you feel it, you see that 2 and 2. Now they only spend their time on FB and anyway. I’m just talking. Those who know how to use it use it, those who don’t, keep it locked, like me with the washing machine. The girl bought me a washing machine, but I’m afraid to turn it on. So I wash by hand, like my mother, like my grandmother, and when my daughter comes, I make her wash too.

Where’s your daughter?

In Novi Sad. She’s married to a theatre director.

How old is she?

Old enough. She’s old enough. She was born in ’57.

Married to a theater director?

Yes, a Romanian theatre director, Iulian Ursulescu. But people aren’t as interested in theater anymore. You have to beat them with a stick to make them go. In our village it was the peasants who used to perform.

Did they let women perform too?

Yes. First it was the female teachers who performed, then other women. Mostly the women who worked, not the peasant women. But we were peasants and we still performed.

Are you tired?

No, I only get tired working. I don’t get tired when I talk.

You wrote here that your father came to Uzdin. Where from?

From Trifoaie. That was the old village. They moved because there were floods caused by Timiș. My father never felt anywhere better than in Cartiz, that’s what the neighbourhood was called. It was separated from Uzdin by a bar. When the waters came one year, that part of Cartiz and our house were hit so badly that the walls came off and my father had to leave the house. He was the first to leave. He had to move out. He was weighed by the thought that he broke up Cartiz, he was the first to leave. His neighbors were fishermen and their group was called the Alăul. I was also born there and when they started bombing Belgrade, my father bought 2 pairs of oxen to build a new house and who knows what else he sold. And then money changed and he lost a lot. Life has its ups and downs.

What do you like better, the ups or the downs?

I think now she would prefer it to stay the same, to stagnate, says Ana Boier.

What?

You want to stay where you are now, neither move forwards nor go backwards.

I’ve got about 200 sayings, 200 wise words in the lyrical folk genre, what else have I got to do? I’ve got some texts in dialect, I’ve got enough to fill my time.

Here’s a comparison that applies to people. Let me recite it to you.

The Angry Hen

Two roosters,

Proud and stocky,

They fought for her sake.

But she,

The fussy lady,

Not at all well-mannered,

Not willing to hear the raucous

Quickly turned her tail to them.

And with a freshly caught earth worm in her mouth,

She clucked with great hatred:

I don’t know what’s the deal is with the motley,

He grumpily wears his garments,

And the white one, dressed as a bridegroom,

Loses his withs over nothing.

Alas, here comes the redhead,

How beautifully he steps,

The red crest hanging,

But what spurs,

What striped tail.

He stopped by the black beauty,

And with a gesture he knows well

Offers her a grain.

Oh, look how he woos her,

They have no trace of shame,

He’s also a scoundrel.

Will you come to Timisoara and recite for us?

Lord, oh, Lord….

Why call out to the Lord?

Well, it’s better to call out to one Lord than to many lords. The world in all its form.

What do you think of the world now?

I don’t like that they’re not serious, especially children when it comes to books and school. I couldn’t stand in school when the teacher asked a child to stand up and answer, and the pupil bowed his head because he didn’t know the answer and keept quiet. I couldn’t stand seeing that. I was crazy about school. But I had no luck. I stayed in the village. I tried to do everything I had to, but nothing brought me peace, except when I picked up a book and read. I was different.

Is Anna Karenina your favorite?

Yes, but it’s not the only one. I read a lot in my youth because my husband read too, and he couldn’t blame me for sitting around and reading and not doing anything else.

Did you use to read aloud?

No, we each read on our own. I couldn’t go to the library in my married woman dress, because I would have been the talk of the village, so he would go and bring books for both of us: “Lord, oh, Lord…only to the Lord we pray”.

What do you think of the war that was here, what’s your opinion after all these years?

…it was stupid… well, I’ve made verses for several rulers, I’ve gone through many emperors, from the Germans till now. Now everyone asks me why I keep so many calendars with Tito. Well, it was during his time that I built a house, I raised a child, I bought everything I needed from the shop. For me, these two, Tito and Iovanca, are an exception. I’ve also read their books—two books have been written about Iovanca—in one they gossiped about her and in the other they praised her.

Do you think that the break-up of Yugoslavia could have happened without bloodshed?

I think it could have and there shouldn’t have been a break-up at all. We had it all: the desert, the mountains, the rivers, just “the ones at the top had no sense and I’m not afraid to say, I’ve only got so much to live, afterwards good bye and good luck”.

Did you get along well in the village back then or was there gossip and talk?

We got along well with everyone, Hungarians, Slovaks, Serbs, even Bosnians. Now you can’t even get along with your brother because there are arguments about one having more land than the other. I once got a slap in the face from my father because I shouted “we want land”. To this day I haven’t forgotten that slap which I got unjustly. Let me tell you how it happened: when I recited, I wanted to recite according to punctuation. My father had been locked up with Păleanu, a rich old man, and one day they meet in front of the town hall and the old man says, Iogo, if your daughter wants land, why don’t you buy it for her? Why did she have to get up on stage and shout that she wants land. My father, who had probably had a few drinks, I don’t know, comes home and I’m sitting at the table, doing homework, and he comes up to me and slaps me. Me, I didn’t even cry, it didn’t even hurt, I just asked why, and he said what’s that about wanting land, I said I don’t know. When God wants to exonerate you, He exonerates you. Incidentally, the book was open at the poem We Want Land and my father saw it. And he went out… He died and he never got to tell me, and I never asked him either why he slapped me.

Where did he hit you?

Over the face. I had just had lunch. I haven’t forgotten that slap. I didn’t get it for being guilty of anything.

Did you talk to your father before he died? Was there anything more you wanted to say to him?

No, I didn’t have anything more to say to him, everything had been discussed. He had tea, laid in bed and died.

Do you live in your parents’ house now?

No, I sold my parents’ house when my mother died because she said I shouldn’t let anyone else live there. I live in my husband’s house, which we built together.

When did you first become interested in the traditional dress here?

I’ve always worn a traditional dress. I like and cherish all my peasant skirts. I spoke to a lady in Bucharest who told me not to write what I think the traditional dress is or how I would like it to be, but to go and talk to the old women in the village while they are still alive. I then went to the grandmother of Pătroi and spent a long time with her. That’s how I learned to write the truth about the peasant costume.

I still remember how I would see them walking and wearing their costumes, I didn’t understand why they wore their woolen skirts like they did. They wore a woolen apron with a golden girdle over it, and I asked my mother why they wore it like that, and she said so that they would shine.

Another cigarette break. Cold coffee. I was left alone with Mărioara and read to her from her book. I can’t replicate the emotion of the moment. I can leave her words here. I don’t know if you’ll ever get to read her book, she had another copy of it anyway, which she carried proudly in her purse.

Photo credit: Diana Bilec

English translation: Cristina Chira