– I had the luck or the misfortune to have been mayor, so I organized many cultural and historical events, it’s about the history of the village.

– When were you mayor?

– After 2000. From 2001 to 2007, I think. I collaborated a lot with Săcălaz, because that part of the village, Toracul Mare, they come from Săcălaz. And we here in Toracul Mic, from the cultural centre onwards, we are from Ardeal. Our ancestors from Ardeal, came here about 25 years before the people from Săcălaz. Because they were busy with animals, with sheep, with cows, this part of the village is marshy and was better pasture. They settled in this part. And when they came from Săcălaz, the people from Banat who were engaged in agriculture, they settled in that part, because the land was better. For a long time, until the First World War, the Great War, as we call it, they didn’t mix, they didn’t take girls with boys from different villages. Those from Toracu Mare had relations with Sărcia and with Ecica, and those from Toracu Mic had relations with Satu Nou and Ofcea, because of the migration that took place then around 1800 – I tell you this data from books in which these things have been researched, such as academician Costa Roșu, professor Valeriu Leu. When they left Transylvania, the first group stopped here in Torac, a smaller group went to Iancăid (Jankov Most), a group stopped in Ofcea, a village near Belgrade, and a group went to a village called Lupulești, in Bosnia. There is no trace, I think there are a few graves left. That’s as far as the people from Ardeal who had to flee because of the reprisals or revolutions that were going on at the time. According to some of my old man’s stories, when Horea came back from Vienna, he spent two days here in Torac.

– And what did you say your name was?

– Ion Ursu. But everyone here calls me Meda, it’s Serbian for bear. When I was in the third grade, there in the center, where the park is now, there was a huge park with big trees, we played football there and we went to drink water, to a friend who had a house nearby. His mother was Serbian, and she asked me who are my parents. And I told her: Ursu’s. Ah, you’re “mali meda“, that means little bear. And since then, since the third grade, everyone calls me Meda, I got used to it. Now I call my son Mihael “meda”. At the beginning, when I went to a place and someone called out: good luck, Meda, wait, they’re not calling me, they’re calling him.

– And you were born here?

– Yes, here in this house.

– And where are your parents from?

– They’re all from here. My grandfather bought this house, but my parents’ house was opposite, where there are some foremen working now. His brother stayed in his parents’ house and my grandfather bought this house from a family that left here for Dobrogea, but they never got there, they went to Lenauheim, and then they had a house in Dumbravita. I kept in touch with them, as I was also related to them.

– Did you go to school here?

– I went to elementary school here for 8 years, in Romanian. I did two years of music school and left it. Then, after I came back from the army, I got my driver’s license, two years at private school. I was hired as a driver and then I went to the Vojvodina Assembly, I drove the minister of Agriculture around for eight years.

And I retired. In December it was a year since my wife died. She was young, nine years younger than me, and she got liver cancer. And there I was left with the children.

– How many children have you had?

– Just one. Because at that time, when I was with Snejana, that’s my wife’s name, she was Serbian… We call Serbs “vinitură“, those who came later, and “old Serb”, those who were colonized earlier. She had relatives in Sânmartinu Sârbesc, in Romania, they say they were family who have been here for 700 years. All Serbs in Banat whose names end with “o” or “ski” are said to be “lale“. Most of them come from around Dimitrograd, who knows when they settled here, and they even went as far as Belgium and took up gardening and flowers and that’s why they called them “lala“, after the name of the flower, tulip.

– And what was her name?

– Costadino. And after her mother was Petro. So they were all natives.

– Did she know Romanian?

– Yes. She went to kindergarten here with the Romanians. She spoke Romanian better than me. She was also declared Romanian.

– Did she have citizenship?

– She didn’t have citizenship, because of the pandemic we didn’t get to do our documentation. But she wanted to become a citizen, she sent the documents to Timisoara, she had to register them with the notary, then get them back and send them to the consulate in Vârșeț. But the pandemic came, my wife got sick and died, and the documents stayed there.

– What documents were to be collected?

– In addition to the personal documents, we also needed proof that you were Romanian, that you were declared Romanian in the census. We also needed documents that you had cultural activity, that you were baptized in a Romanian church. She was baptized at the age of 30 here in Toracu Mic, at the Romanian church.

– In the beginning where was she christened?

– She wasn’t christened.

– Why not?

– At that time her parents were party members and they didn’t look kindly on party members baptising their children. Her grandfather and grandmother in Jitiște (Žitište) were people who went to church regularly and she thought that maybe they had baptised her as a child. And she asked, because it’s bad luck to be baptised twice, and the priest in Jitiște looked in their baptismal books and said she wasn’t baptised. And then she was baptised when Father Musta was here. She was in Germany, to her aunt’s, and came here to be baptised, so that we could be married in the church, because we were only married at the civil wedding. We had to be godparents to Măran. And Măran had a wife from Romania from Satu Mare and we couldn’t be their godparents at the church because we weren’t married. And we couldn’t get married because she wasn’t baptised. And so we took it step by step.

– You said she was away in Germany?

– For the last five years, every three months she went to Germany and worked there. And just when the pandemic started, she went there and was allowed to stay, she had the documentation done, she just had to register to an office that receives foreigners – I don’t know how is it called in Germany. But that office closed with the pandemic and then she came back from Germany and was waiting for the office to call her, to go back. Along the way we found out she was sick… and how we found out! She had to go to Germany on 6-8 September and on 4 September we went to get her blood tested, an ultrasound, that she had a stone in her gallstone. And when she did that ultrasound, the doctor said: you have something else, let’s see. And when they did the biopsy they saw what it was.

– Nasty disease.

– The boss of this private hospital was her classmate in ninth and tenth grade. He is a doctor, so we went to see him. And he told her: Snejana, I have no words, what to tell you. And our doctor Gabi referred us to Novi Sad, and the doctor, when he saw the results of the test, said: Snejana, get your work done as soon as possible, otherwise you’re gone in three months. And so it was. She went to the doctor on September 4th, the results came back on September 20th and on December 12th she died.

– I would like to ask you: I understand why young people want so much to obtain Romanian citizenship, because it is easier to go abroad to work, but why did you want citizenship? How does it help you?

– Let me tell you. Here in the village, before the Second World War, there used to be teachers sent from Romania on the basis of a contract between two countries, an exchange of teachers. Many teachers who came here were legionaries and they made a big nationalist propaganda here in all the villages, not only in Torac, but in Torac they had extremely good roots. And I was brought up in a family where it was an honour to be a legionary. I learned the nationalist songs that the legionaries sang in those times from my grandfather, from my father, and they are still in my heart.

I married a Serbian. My child also married a Serbian. We don’t mind that. I was born here. Since 2013 I listen to Andra and Adrian Daminescu and when I hear those… now of course, when a man is older, he is more sentimental. And when I hear those songs, with St. Mina, or „Cross the Carpathians Romanian battalions”, I’m ready! Because that’s how we were brought up as children. They taught me Radu Gyr’s carol, „A venit și aici Crăciunul” (Christmas has come here too), only we sang it to the tune of „O, ce veste minmunata” (traditional Romanian carol). And then we saw that it was the other song. And when we were in the council choir, we had a choir party before Christmas and we started to sing „Christmas has come here too” and one of the men from Sânmihai said: „You guys shut up! I’ve never heard it like that”.

– Do you sing too?

– Not now. I’m a choirboy, a church stranger. But now I have a problem, I have my teeth out because I want to get dentures, and often when I want to pronounce it doesn’t come out right.

Doru Ursu (DU): These legionary songs were banned in Romania during Ceaușescu’s time and it happened that the boys, their generation, when they were in Romania, they drank a bit and they started singing in the street. And then Securitate (Secret Police) came and warned them that it was not allowed. But I think that the Romanian people were also keen on these songs.

– I went to Zalău in 1981, to an acquaintance, the man wanted to treat us, we ate, we drank a few glasses and started singing. And he opened the windows, he lived on the third or fourth floor and said: Boys, please sing as loud as you can. Why? There’s the Secret Police on that street, let them hear who are truly Romanians.

DU: And it’s interesting that at parties and nowadays, as I said, beautiful repertoire, the local repertoire, and the Romanian repertoire, but every time we start singing these patriotic, legionary songs, you see people react otherwise, they immediately get up from the table. They had a different effect.

– And what songs do you sing? What are the ones you like?

– “Don’t forget you’re Romanian”, which is sung here not as Furdui Iancu sings, but to a different tune. “From the Danube to the Seine”.

I’m listening now to the taraf playing at the girls’ fair on Mount Găina. And Bocăluț (the conductor of the Lira orchestra, who was a virtuoso, a man of culture) played all those songs 50 years ago, but there was no internet, radio, television, where did he get them? They brought them with them.

The neighbouring village, which was a German village, after the Second World War the Germans swept them away…

– To Sarcia?

– No, to Krajišnik. And the village was settled by Bosnians from Krajina, from Bosnia. They always were in favor of Tito. Around 1970, it was the director of CAP (cooperative farm) who organized, put money and built a gas station, a butcher’s shop, a fish market, roads, asphalt, aqueduct, everything that the village needed was done. And it’s May Day, all the officials on the official platform and passing people in a parade, but without music. They’d need a brass band or something to play marches. Lira, which is the only band here in the region, went to play marches, if that’s what the party says. And how would they know Serbian marches? They knew how to play legionary marches. And Bocăluț said: let’s go and play. If they lock us up, they lock us up. And they started to sing legionary marches, about partisans, to Romanian music. (laughs)

– Did you play any instrument besides your voice?

– No. I went to music school, three years I learnt the piano, one year I learnt the violin, but I didn’t advance much.

– Did you go to Romania before the Revolution? What were you doing there?

– Yes. We were young and we used to say, let’s go to Jimbolia to a café or a disco. At that time we listened to a lot of rock from the West. And in Romania they didn’t even dance like that. When a boy of my generation danced with a girl, it wasn’t a waltz, but in that rock style. And when they saw that we started jumping around like savages, they stopped the music. Then we felt a bit silly, we didn’t really mean to interrupt.

I was a rock fan before the army, I had big hair up to here, I had a leather jacket with writing on it, and when they saw me with that… I went and left it in the car, that you felt uncomfortable, how they looked at you.

– But you didn’t have any places to go out here, did you?

– Well, we needed to get out for a bit. And secondly, a lot of things were a lot cheaper. For example, at that time we brought canned food and salami from Sibiu from Romania. There were many kinds, but they didn’t have good quality.

– Did you take anything from here there?

– I didn’t bother with that, but my friends brought jerseys, chewing gum, cigarettes, vegeta, pudding. But in 1981 when we went to the Black Sea we sent seven carpets from here by post to an acquaintance in Buteni. And they picked them up there, paid the customs, then we gave them back the money. We sold them, we made a lot of money on them and with that money we went to the seaside. So, to make a comparison, at that time it was 72,000 lei a Dacia. We had 48,000 lei and the three of us went to the sea. And we couldn’t spend that much. We went camping at Eforie Nord and left the car in the parking lot. Sima had an old Moskvitch, couldn’t lock it, we left it open and the money in the car. No one came near it when they saw it was dirty and old.

– But how could you leave it like that?

– Well, where are we going to take it? If we’d taken it to the campsite, we’d have left it there when we went bathing. I’ll leave them in the tent, you can’t close the tent. He had the car, where the gearbox is, you could lift a plastic lid to pour oil for the differentials. So we lifted that plastic, put the money in and that was it. But no one broke into the car.

– What was your perspective from here to Romania? How did you see Romania before 1989?

– I had acquaintances who explained things to me, because I didn’t understand, I didn’t have the experience of life. For example, the CAP (cooperative farm) chief in a village near Kikinda had two six-row maize harvesters, made in Romania after the French licence. When I saw those at his place, I said: if I had those at our place, I would have made a fortune. He said: they’ve been sitting for two years, we don’t use them. Why don’t you use them? He said: if I use them, I need two drivers on them and I need 4-6 more drivers to do the transport and I’m done picking corn. But what do the other people do? So they all have to work by hand, they get paid for what they pick by hand. And leave a parcel of 20 feet where they don’t pick up the corn and come in the evening and take it home, so that they have to raise a chicken, a pig… we all have to live. And I thought: look how the man thinks, he takes care of the whole village! It’s not just for him, everyone has to live.

Then I saw the same thing in Buteni, with their boss from CAP, I asked him: how do you work? We have cows, people have buffaloes. When spring comes, we don’t have enough hay for the cows, we borrow from the people, the people give it to us, and then we return the hay to the people. If we don’t have enough to return the hay, we also give them a cow, because everyone has to live. That fascinated me.

– Was life better in Romania then?

– No! Let me tell you, in those parts near Buteni I saw the first private tractor. In Romania there was an older tractor, bought from CAP, but it was private. So there was no full collectivisation there. And where there was not full collectivisation, people lived better. Here in Banat, where there was full collectivisation, they had a hard time. That’s how I saw it.

– And where were you during the Revolution?

– During the Revolution I was in Germany.

– Were you following it, were you aware of it?

– Yes, I was. I don’t know German. I watched TV and at that time the Germans had round tables where they discussed the union of Europe. I liked the history, I liked the geography, but it wasn’t clear to me how they wanted to unite Europe because the borders were close like Austro-Hungary was. And I waited for Snejana’s aunt or her husband to come home from work to translate for me. And when once, hop! In Romania it’s revolution! Then the Germans showed everything, and how there were shootings in Timisoara. All the filming went through the consulate in Yugoslavia, the consulate in Timisoara passed it on.

– And how did you feel?

– At the beginning… look, even now I got goose bumps. Then when I thought about it, as mr. Rancu said: the Coca Cola revolution. And I didn’t understand what he meant. That man, who was a thief and everything, was imprisoned in Romania, he had his own system of thinking and he said that other people financed the revolution and organized it, not the Romanians. Then I began to believe it was. The Romanian people were screwed.

– After the revolution you were in Timisoara?

– I haven’t been for a long time. I went to Ilie’s child’s wedding. I knew Timișoara well enough, now I can’t find it again. Timișoara changed a lot after the revolution. I know we went with Snejana to the wedding, then my child had a BMW, it used a lot of petrol, we drove to Timisoara, we found where the wedding was, we parked, but we didn’t lock it. And I said, forget it, God forbid, someone steal it. (laughs) I didn’t have any bad experiences in Romania, neither during Ceaușescu’s time nor after. But after that I didn’t even work in private companies, I was with the choir, with the carolers’ group.

– Have you ever thought of moving to Romania?

– You know what? For a while I was quite angry with Romania. I mean, not Romania as a country, but the people who run it. I had the opportunity to talk to some ambassadors, consuls who were here, in Belgrade and in Vârșeț: you should keep your tradition, the Romanian language, but be loyal to the country where you live. How did Romania help us? Apart from what I brought from Săcălaz and my friend Ilie financed from his commune, we brought poems and stories for the kindergarten, but Romania… nothing! Now they give citizenship, but in Romania they gave citizenship before, but not to the Romanians here. And I think they wouldn’t have given citizenship here either, if they hadn’t had to give citizenship to the Romanians across the Danube.

DU: And I also said, it’s a pity that the others unfortunately don’t want to declare themselves Romanians, they are Vlachs, they say. And they don’t declare themselves as Vlachs either, but Serbs. But we are here and we speak Romanian all the time, on the street, school in Romanian, church in Romanian, Romanian families, Romanian customs…

– Before my wife got sick, I went to Alba Iulia and bought one of those belts. And I told her: now when I go to Romania for the second time I want to get a shirt from the national costume and when I die, I want you to bury me in those. She said to me: do you want to be buried as a Romanian? I didn’t feel any help from Romania, from the mother country, neither personally nor in society to do anything. Maybe in other villages and other places they did, but not here.

– Where did the child go to school?

– The child went to school here in Serbian.

– Why in Serbian?

– It was easier for him because I drove the truck and I was in the field for a long time and at his mother’s to help him, it was easier for him in Serbian. Then he had to continue school here further, middle school. I had problems when I went to school, because I knew Romanian very well, but when I went to middle school, I didn’t know Serbian terminology in basic subjects. It confused me. In chemistry the teacher put a problem on the blackboard, who knows how to solve it? I raised my hand, I knew how to solve it, but the lady said: you do well, but tell me! Well, I don’t know how to tell, because I learned it in Romanian.

– And the child spoke Romanian?

– Yes, he did. At home he learned with us.

There was an inquiry in our country, about what the country is doing for the citizens of the diaspora, the current regime made an inquiry, because if there were early elections now, who would you have voted for? My daughter-in-law said: for Hungarians. I don’t know the name of their party. Why? Well, I would have voted for another party that would have fought for its people, as the Hungarians fight for their people. And what is your origin? Bosnian Serb. She left them speechless. Because they didn’t expect a Bosnian Serb to respond like that. If they had done in Romania what Hungary did for the Hungarians here, it would have been a different story. I don’t know what’s stopping them, that conflicts between countries shouldn’t happen because you help your people. I am Romanian, I like Romanian identity, but Romania as a mother country has done nothing, not for me, not for my family, or for the citizens of this village.

– And where were you going with the orchestra?

– I didn’t go to the orchestra, I went to the choir. I used to go with the choir to Buteni, in Oltenia, Craiova, Drăgășani…

– And in Serbia?

– I haven’t been to Serbia much. I went to the festival in Zrenjanin… Now in this choir that Doru conducts, I think he takes us to many places.

– Are you also in this choir?

– Yes, but I’m a bit old.

– And the other choir, why doesn’t it work anymore?

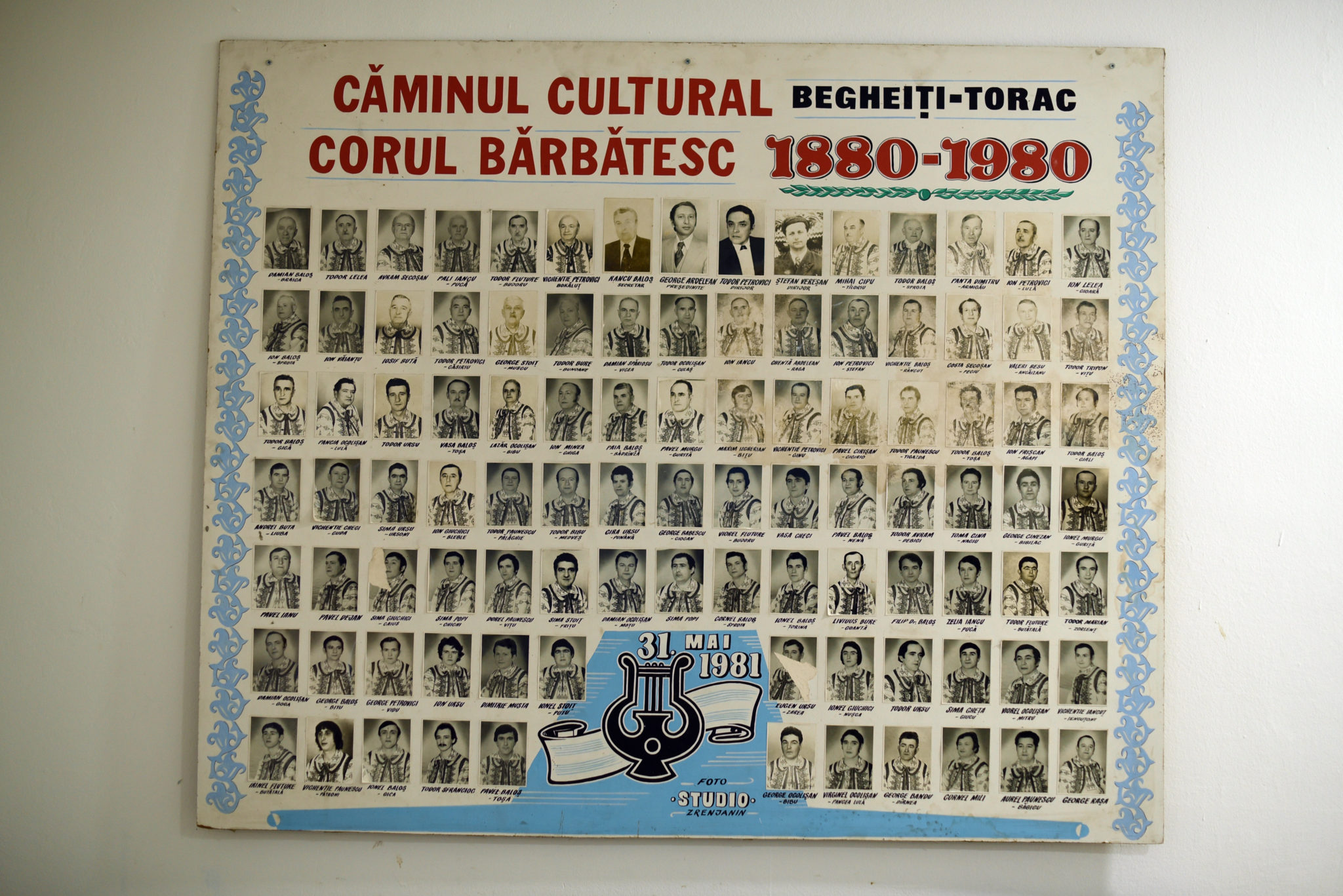

– The other choir used to be a choir of 80 to 120 people and they were all farmers, amateurs, and they made it all the way to the festival in Nis where they got first prize, they fought with the professionals. They were good people, good singers, only those generations of people are gone.

DU: (plays a recording of the new choir) It’s an amateur choir and since they don’t come to rehearsals regularly, they sing worse.

– We didn’t sing worse, we just got better and better. (laughs)

DU: The mixed choir of Torac – that’s how you find it.

– And with the old choir we find recordings?

DU: Unfortunately only one from Coștei, from the 1975 festival (plays a recording).

– That’s when my father sang, older generations sang.

There was a festival in 2002, I organised it in Torac and some guys from Pro Tv International came and took interviews, you can look it up.

DU: There is also a girls’ chamber choir conducted by Mrs Georgeta Ocolișan, she has some recordings, you can search. She is away in America. After that I also did a chamber choir for girls, very good. After that I stayed with the mixed one. I’m always attracted by what’s more complicated to work with, with a mixed choir it’s very difficult to work with the voices, to homogenize them. Then there’s the Lira orchestra and our dancers. On the website of the cultural home – ACR Bocăluț.

– Where’s the mother from?

– From here, from Torac. And my father too.

– And what did they do?

– Farming. Most of them were in agriculture. Only lately some of them have prospered and have taken up land. My parents stayed that way because after the Second World War the land was confiscated. My grandfather was a teacher and the communists wanted to shoot him because he didn’t want to give a hectare of land to the country voluntarily. My grandfather said: you still take it, but I won’t give it to you voluntarily. This one took out his gun to shoot him, he hit him over the hand and shot him in the ceiling, in the house. I was little and I didn’t know why that hole was made and my grandfather told me. And until 1968 when my sister got married, they weren’t allowed to cover that hole. Even that man’s son child felt guilty, because look what his father had done and he wanted to fix it somehow. You can’t fix that, that’s it, cheers. There were a lot of hard things and that’s why I decided afterwards that farming was hard and I couldn’t resist any longer and I went to work as a driver.

– And now who’s in charge of the land?

– Me and my son, we don’t have that much. Now we have clover and the land is very dry, hard. If it rains, it’s done, but if it doesn’t rain… I just went there to take out the weeds.

– What else can people do around here if not farming?

– At the moment, apart from farming, I don’t think there’s anything else. There are some who are employed in various jobs, but otherwise, not really.

– And the children didn’t want to leave the village?

– They wanted to at some point, they even rented accommodation in Germany. She had an acquaintance, some older people, who were willing to finance her, to pay for the housing for three months before, to buy them some furniture. When the pandemic happened, she got sick and died, then they decided to stay here, and Mihael took a job as head of the grain bins. And Jelena didn’t get a job, she takes care of the children, makes food. I help her out as much as I can, I do the cooking.

– What do you cook?

– My mother taught me, she was sick for a long time, when I was younger, seventh-eighth grade, after my sister got married, my mother was in bed and I asked her: how do I do that, how do I do that? And I learned how to make food, traditional food, which they make at home. I’m absolutely not afraid of any woman for doing better than me. When I was young, my sister was married in our village, but she didn’t come here much, she had her own house, her own chores. And I wanted to eat something sweet, I would eat a cake. I ask my mother: I want to make a cake. She says: do like this, like this… And as she told me, I did. I made the first cake on Thursday. My sister came to my house, here in this old house, my mother was in this room, in the middle, she was sitting on the bed, my sister was talking to her for a while, I made a cake. My sister said: I’ve got more time now, I’ll make you a cake, I said, you don’t have to. She said: who made that? It was the simplest cake with cherry, cornflour, baked in the van, you turn it over, put cream on top, I mean whipped cream, and that’s it! Then I made more combinations, with vanilla cream, then I specialized in cakes. (laughs) After Mihael got married, Snejana went to Germany, Jelena knew how to make, just forget it, the old man does it. I made a cake and I said to her: my hand is shaking – this is a family disease in our family, my mother, me and my cousin – you just cut it. Jelena cut it nicely, took it out of the pan and took it to her mother, she said: when did you make it? I didn’t, Meda did. (laughs)

– Jelena came with some of her traditional food?

– Yes, some of her specialties. But I can’t translate them into Romanian. There’s not much difference between their food and ours. They generally eat a lot more meat than soup and broth. They make a kind of… it’s not a cake, they make a kind of dough, like a pancake, then they put it in pan and on top they put grated cheese, they bake it. That’s their traditional recipe. Otherwise the food is pretty much the same. They eat a lot more piglet on the grill. It’s much easier, now that it’s automatic, you turn it, in four hours it’s done, just grease it once in a while.

– Where did they meet?

– Jelena grew up here, she was two years old when she came.

DU: They met because they were here in the village, we all went to discos, cafe-bars, we were in the gang together in the village. And when you’re young, you go to a cafe bar to hunt, naturally, you happen to like a girl you like and that’s it.

– And how did you and your wife meet, did you go dancing, playing?

– My wife used to be in the group of Romanian dances, she has photos of how she performed. But no, I met her much longer ago, at Bega, we bathed and her house was nearby. We met when she was no less than 15 years old. And we went out and we broke up and we were together again. I’m telling you, she was the initiator. She came to me, I worked in agriculture then, I wasn’t employed, in the fall, I picked corn, I had to get it up in the cornfield, the next day get up at four in the morning and start over again. She came to my house, she waited for me, let’s wash up, let’s go. I told her: I’m not going to accompany you at home again. Make up your mind! If you want to come here, come. Either stay or go alone. She: Come home now, I’ll stay on Sunday. On Sunday I went after her and brought her, without any luggage. Her mother told her, you didn’t take anything, not even pajamas. She said, “No, I brought two pairs of panties. (laughs) Before that I wanted to go to her parents to ask her nicely, but she didn’t want to.

– Why?

– She was afraid they would stop her. But her father wasn’t dangerous, he was more serious. Well, I get along well with her father, I was with him in the pub. He convinced me, he stayed with me for days and drank to make me a member of the party. I don’t want to. And two days after she stayed with me… that evening I sent my sister and my son-in-law and a cousin with my wife and they went to her parents and told them she had stayed. And then two or three days after that we went to them too, it was ok. On November 29 this happened, on December 24 we had the wedding.

– How was the wedding?

– The wedding was great. It was in that hall of the cultural centre, which now is run down. The only mistake I made was that I wanted to do it on Christmas Eve, but they don’t do weddings on Christmas Eve. I just didn’t know, and no one told me. But I wanted to do it before New Year’s eve. We couldn’t get it organized so quickly. And then we organized at the restaurant in Jitiște, food, waiters and all. My wedding was the first one in Torac where there were hired, paid people (waiters), so everyone could enjoy themselves. Before they used to have weddings where relatives and friends helped (served at the tables). Not at my wedding. Nobody helps me, I will pay, I have no obligation to anyone. There was singing in Romanian and Serbian. It was Grumă’s orchestra from Ofcea, because at that time the Lira orchestra was not so active. I know that Grumă did 16 exercises with the orchestra, he brought a taragotist from Barițe, an accordionist from Albunar, he gathered a good team and said that we had to practice because we were going to Bocăluț’s village. You can imagine, Bocăluț was so respected, you couldn’t go there to make a fool of yourself. First he told me a price… he asked for a lot of money, that I might reject him, he didn’t want to take over the obligation. I said: good!

– What’s the wedding tradition? How did it go? With the dress, the food?

– That depends. For example at my wedding, the bride was in her wedding dress, I was in my groom’s dress.

– In a suit or in a folk costume?

– In suit. Before, it was a beautiful ceremonial that has been preserved. The wedding would last for three days. It was organised at home. When they came for the bride, first the bride stood at the entrance to the wedding hall, there was a woman guarding her, all the groom’s groomsmen came and shook hands with the bride, kissed her and gave her a penny. That was money – coins. There were many of those customs.

– Do you have any old pictures?

– I have lots of pictures, old and new. Let me ask Jelena to get the albums. I’ve got pictures from the wedding and activities. With the long hair and the leather jacket I don’t have photos. When I came back from the army, still with a haircut, the neighbours were saying: what a handsome child Todor Ursu has, he never saw that hair. I also have pictures when I was an actor.

– Where were you an actor?

– Here, in the theatre department. But I’ve also been in elementary school. Then in 70-something in Alibunar, when Ioniță Băbescu took first place for the role he played, I took third place. I played the man from Mars. I had quite a rich activity. But I didn’t get to dance, I was in the choir and the theatre section, I had enough.

– How many granddaughters do you have?

– Two.

– Do they know Romanian?

– So-so. I speak Romanian with Grandma Tita, they speak Serbian with me, and I answer them in Serbian. It’s easier for them in Serbian, they’re used to it. Just now Jelena has drawn Tita’s attention to the fact that it’s very important that she speaks strictly Romanian with them. If they don’t understand something, she translates for them.

DU: I mean, there are people who don’t have this problem, that they are Serbs and they have to change the language. Many girls or women who were married into Romanian, Serbian families, who spoke only Serbian all their lives until they got married, learned to speak Romanian and speak the Serbian language.

– Like Jelena. She’s a little ashamed to speak Romanian, because she’s not sure of some things.

(show pictures)

– How long have you been an actor?

– I was for many years, in many plays. I’ve been gray and handsome, now I’m not young anymore, but I’m still handsome. (laughs)

– Where did your wife get her wedding dress?

– She bought it in Zrenjanin.

– And she kept it afterwards?

– I still have it. I’ll show it to you. The wedding dress is for rent now.

– What year were you married?

– 1983.

– Where did you serve the army?

– I was three and a half months in Szombor and then Krško in Slovenia.

– When there was a war, did you participate?

– Four months.

– Where were you?

– I was in the reserve near Vukovar in Croatia. But we retired…

– Do you have folk costumes?

– I don’t think there’s anything left. Baba Tita said she’d show you. There are many families who have folk costumes in the house, especially families where there were girls.

– Didn’t you tell me your wife came with a dowry?

– I told you, my wife when I brought her here had only two pairs of panties. (laughs)

DU: In those years they didn’t pay much attention to that stuff, already in the 70s and 80s weddings were different. Before, old weddings lasted a week, from Tuesday to Tuesday.

– With my child it was like that. The wedding was in one day, the party at the restaurant, with 400 or so people, just before the wedding a few days and after the wedding a few more days, there was a party here in the courtyard, music… I also want to say that among all the other drinks that were drunk, wine, beer, sodas, they drank 86 liters of brandy (țuică).

– What kind of brandy?

– Grape brandy. There were so many people and how much fun it was! We didn’t drink so much before the wedding night, more juice, beer.

I have a child and I was fond of him and my daughter-in-law. I think before the wedding he was with several girls, I don’t know, he didn’t bring any girls home. I told him: you don’t bring a girl until you say, that’s it, she will be my bride. And when he came with Jelena he said: That’s it. I said: I know! (laughs)

(brings in the brandy and they all taste it)

– You can feel the grape and how soft it is.

– It’s good and sweet, but it takes you away.

DU: There’s a big difference between the brandy that’s made in Romania and here. Three are my favourites: the grape, the apricot and the quince.

– Which do you like best?

– The grape. And the plum. In quince brandy, if you don’t put sugar in it, it doesn’t do anything. I have a doctorate in making brandy. (laughs) People make brandy out of myrobalan or apples because that has no taste, no smell and then they pour it into the quince brandy just to have that flavour.

– For example, from 100 kilos of quince you can make 5-6 litres of brandy. And from 100 kilos of grapes you make 20-25 litres.

– (speaking of food on the table) Is this made from your pigs?

– Yes, it’s still homemade, to tell you the truth, we don’t buy much. And the bread is homemade. We just cut a pig yesterday.

In the 70s and 80s I went to Timisoara and brought back salami from Sibiu, canned ground meat, a superior quality, we couldn’t find such quality here.

DU: We are lucky with our butchers, we still have, one – two – three in the village, who know how to make baloney or salami like that.

– They are very good, just listen to the old man, it’s proven that everything they make, baloney, pressed ham, they put additives and nitrites in them, which are very poisonous. The sausage like I make it, you can’t buy it anywhere.

– How do you make sausage, what’s the recipe? Or is it a secret?

– It’s not a secret, I don’t like keeping secrets, why not tell people? Salt, garlic, pepper, paprika and a pinch of sugar – to help the fermentation. I experimented before and then I told my child and Cornel (my sister’s nephew) and they wrote down the recipe, because I’m getting older and I don’t remember the right amount.

My daughter-in-law is currently making cheese too, but she’s sold it now. You haven’t had any of that cheese.

– What kind?

– Cow. My daughter-in-law makes sweet and salty cheese. Her parents had 70-80 cows. They came in the 90’s, during the war in Bosnia, they had to flee from there and they had to start working something and they got busy with animals. Jelena was 2 years old when they came here.

– So she was born in Bosnia?

– Yes, she was born in Sarajevo.

DU: It was a disaster there. Very stupid. But what can we do?

– When I was younger, I loved reading and I read a lot of books. And then I enriched my vocabulary and I wasn’t afraid to speak Serbian and Romanian. Now I have lost some words in Romanian terminology because I don’t have the opportunity to use them.

In 2002, we organized the music and folklore festival in Torac and then two guys from Pro Tv International interviewed me. And I said: I’ll give you the interview on the condition that you give the interview entirely as I say it. If you cut it out, don’t do it at all. And they didn’t. Because I criticized the mother country.

– What did you criticize? If you can say…

– I’m not afraid, nobody can do anything to me at 70. I criticized the mother country for not helping us. The ambassadors and consuls came and just patted us on the back and told us to be loyal citizens of the country we live in. It’s nice that we are Romanians, it’s nice that we keep the tradition, it’s nice that we keep the customs. We wouldn’t even have citizenship if there hadn’t been pressure on us from across the Danube.

– But who would manage this help id from Romania?

DU: It depends on how the link with Romania would be made and over whom. In fact, the main organisation or institution that should have coordinated all the Romanians here is the National Council of the Romanian Minority. Before the National Council there was the Community of Romanians in Yugoslavia or Serbia, which all our people from Torac set up. And then started a dispute between the regions unfortunately we Romanians are split in two.

– Where is this council based?

DU: The headquarters used to be in Novi Sad, but now since this political leadership came, wanted to move it to Vârșeț and they moved it. And they want to move all the Romanian institutions to Vârșeț. There are Romanians in the central Banat, near Zrenjanin, not only near Vârșeț, only in smaller villages.

– The number of Romanians may be higher in central Banat than in southern Banat.

DU: Whoever can say what he wants, like the gypsy who praises his horse, I praise mine, because the people from the central Banat are much smarter than the others.

– Our ancestors who were expelled from Transylvania and came here said: stay at home and mind your own business, stay out of it, you can’t do anything to them… because they were afraid. And this has remained with us from generation to generation.

DU: We actually have rights from the Serbian state.

– What rights?

DU: The same rights for everyone: to have school, to have church, to wear the folk costume, the customs, the festivals, the most important things. We have the longest-running festival in the Balkans – 62 years, the longest-running orchestra – 95 years of uninterrupted activity.

– Do you know when the Cultural Centre was built?

DU: I think around 1950-60. In the 1980s it was extended and this bigger hall was built. In 1930-40 the Cultural House was built.

– The Cultural House was built in 1942, when the Germans were here. There’s a project to renovate it.

DU: The financial resources are with me at the institute.

– After the war, in 1950-51 the Cultural Home was built. Because until the Second World War there were two villages, Toracul Mic and Toracul Mare. Where the Cultural Centre is, where the park is, there were pits, swamps. After the war it was only in 1946 that the two villages were joined together, Torac and then they changed the name Begejci (Begheiți) and then the Cultural Centre “of cooperation” was built, where there was a performance hall and on the other side, towards the school, there was the agricultural cooperative. Then they moved into those old buildings and for a couple of years they put wheat there – when Sârbovan was director of the cooperative, he brought new varieties of wheat and they had nowhere to put the wheat and they put it in the Cultural Centre, in the room where the counters were. And here is the Cultural House. And then the priest Ion told them off, because the church in Toracul Mic was the initiator of the building of the Cultural House.

– So the one from 1942 is the Cultural House.

– Yes. And this is the Cultural Centre. After the villages were united, the park was built between the villages, the centre.

– These cultural centres were built according to a national plan, like yours, I guess. Is there a program at the Cultural Centre imposed by the state?

– No. The President and the Board of Directors decided. In those days when the hostel was built, it was registered as an institution and had a director, three employees and was funded from the budget. Then it was not a commune, but a municipality. Then in the 70s, when the financial system broke down, that’s when they changed.

DU: And nowadays it works pretty much the same way, with a director, a board of directors, only it’s voluntary. And we do our program and plan, honorary. For example, if I want to give a concert at the Philharmonic in Arad, I get in touch and tell them and I invite myself. And when we go there we have to prepare, rehearse, to do something qualitative, to impress. And that’s how the collaboration started. We are the initiators of a festival in Dudești. There are these very strong links between us and Romania.

– Have you also performed privately in Romania, I mean at weddings etc.?

– In Romania I went to the wedding of the mayor of Săcălaz’s child, I didn’t go to others. But I didn’t sing, I was a guest.

DU: I was, because it was my job, but it’s interesting that it didn’t work for the Romanian people in Banat, because now at weddings they ask for Serbian Gypsy songs, they ask for the saxophone. Anyway, they are all good musicians. My colleague Roman Bugar and I have tried to do it, we went to weddings in Romania for a couple of years, with two formulas. In the first formula we had: double bass, cymbal, taragot, violin, soloists, where others who heard us were astonished, because in Banat they had never heard anything like that. In Bucharest it’s different, it’s full of drummers. They also go to the resorts only with the dulcimer. Unfortunately, not in Banat. People who saw it said: yes, yes! Unfortunately the organizers I went to said: you see that doesn’t work. The second formula we went with the organ, I call it the morgue (laughs), the saxophone and go, go, go, that works. I understand that that’s required in the 21st century. Unfortunately in the Romanian Banat Serbianism and Gypsyism have started to enter, which bothers me. Marian the Mexican said in an interview – I can go and play in Serbia, but I will never play Serbian music the way a Serb plays it, just as no Serb can play the Romanian music I play. Of course! That’s what our guys do, they all want to be great. No, keep what’s yours, that’s why we’re Romanians. All the newly composed songs are Serbian. That’s what bothers me.

The people from Toracul Mic are very cheerful, they know how to party. I had to sing much louder than twenty of them for them to hear me. Every time I switched to legionary songs – “Don’t forget you’re a Romanian”, “From the Danube to the Seine” – people went crazy, they felt they were Romanians. The people from Toracu Mare are not like that, they are a tamer breed.

– They’re from Banat, and the Bantian people are slower.

– They were good singers. It happened once in Iancăid, they went to a funeral, and there happened to be four choristers from Torac, and they sang four choristers in four voices.

DU: Tenor I, tenor II, baritone, bass, each on his own voice.

– People like these are not born anymore. At that time there was no television and then they met and sang.

DU: Before being a chorister was like having a rank, being a general. It was an honor. I only want quality, because that’s how I was used to it. It bothers me when I hear other villages singing falsetto, unison, it gets on my nerves. I’m used to hearing quality, clean, three or four voices. That’s the way I grew up and that’s it, I can’t change that. That’s my professional flaw. That’s why I do serious rehearsals, like only national choirs sing.

– You were also talking about Furdui Iancu’s piece…

DU: Yes, “Don’t forget that you are Romanian / For if your father is a shepherd / Your grandfather was Traian / And in this country alone he was master” (sings). Furdui Iancu sings it slower, we give it some energy, we don’t wail it. (laughs).

– For example, many people don’t know how to sing the third or fourth stanza of this song from Moti Country: “To Neamt, to Tutova we came / Great battle we won, we won”. The thing is that in Neamt and Tutova the Legionnaires won, they had a majority in Parliament because they won the votes and they turned this song. And many sing it, but they don’t know what it means.

– Did you do history at school? History of Romania.

– No. Unfortunately, no.

– And you read it yourself?

– Yes. I’ve also read the history of the Middle Ages, and ancient history, all the history books I’ve read. My sister also went to the normal school, to the teachers’ school in Vârșeț, and I also took some books from her. And then I drew some conclusions, that not everything is written in the books. You have to make up your own mind about some things.

We used to sing: “with Tito always leading us”. That was an interesting song in those days.

– And what was that song like?

– “If ever the enemy should succeed in defeating us / We’ll fight like never before / With Tito always leading us” (sings) It was in a more march tempo and had a text, I don’t know who wrote it, Radu Flor, I think. I remembered this one: “O Lord, from the blue skies / Do Thou also take care of us / And find us our sorrows / And save us from war. / Come poor, poor peasant, long-suffering / He cares, but life has not, till death he owes.”

DU: “Captain Ciulei’s Ballad” – it’s Moldovan, but it’s made it to our parts.

– “Through fairy-tale snow, from Vaslui towards the Carpathians / Through the snowy wilderness goes a sad convoy of soldiers / They have sorrowful faces and on their foreheads is cloud / For they have orders to execute a commander of their own” (sings)

I also know all of Tudor Gheorghe’s ballads.

– So we have to come back. And you have to come with the choir to Timisoara.

Photo credit: Diana Bilec