I met František Kuska a long time ago, in Bucharest, at the Days of the Czechs in Banat, a celebration through which we wanted to make the Czech community better known to Romanians. The six Czech villages in Banat are visited every year by thousands of tourists from the Czech Republic and by the Czech press, but very little is known in Romania about this community that has lived here for two centuries and has preserved its language and traditions. František came to Bucharest to play with the band from his village. I organised the events at the festival. We have been in touch ever since.

We met again at his home in Gârnic, his native village. He is the sixth generation of Czechs living in Banat. We loved the rosehip jam made by Maruška, his wife, and every time we went, we stayed with them, we drank țuică, and we talked about village life and city life. I felt that their life was there and that they were doing relatively well.

About a year ago I saw František share his location on Facebook. I had a quick look at the comments and realized that František and his family had left Banat. Like many others in his generation. A year later, I was curious to go and see the place he had moved to.

His home village of Gârnic is surrounded by a dreamy landscape, hills and mills. I was surprised when I arrived in Strašice, in a picturesque Czech village with a pond and wooden houses. Above the houses, after a bend, I found František and Maruška, in a farmhouse with a courtyard, not very different from the one in Romania. Only the animals were missing. František greeted me saying: “Welcome! We live here the same as in Gârnic! You’ll see, we have wooden stoves, garlic, tomatoes in the garden, and we’ve just come back from picking cherries!” He was laughing.

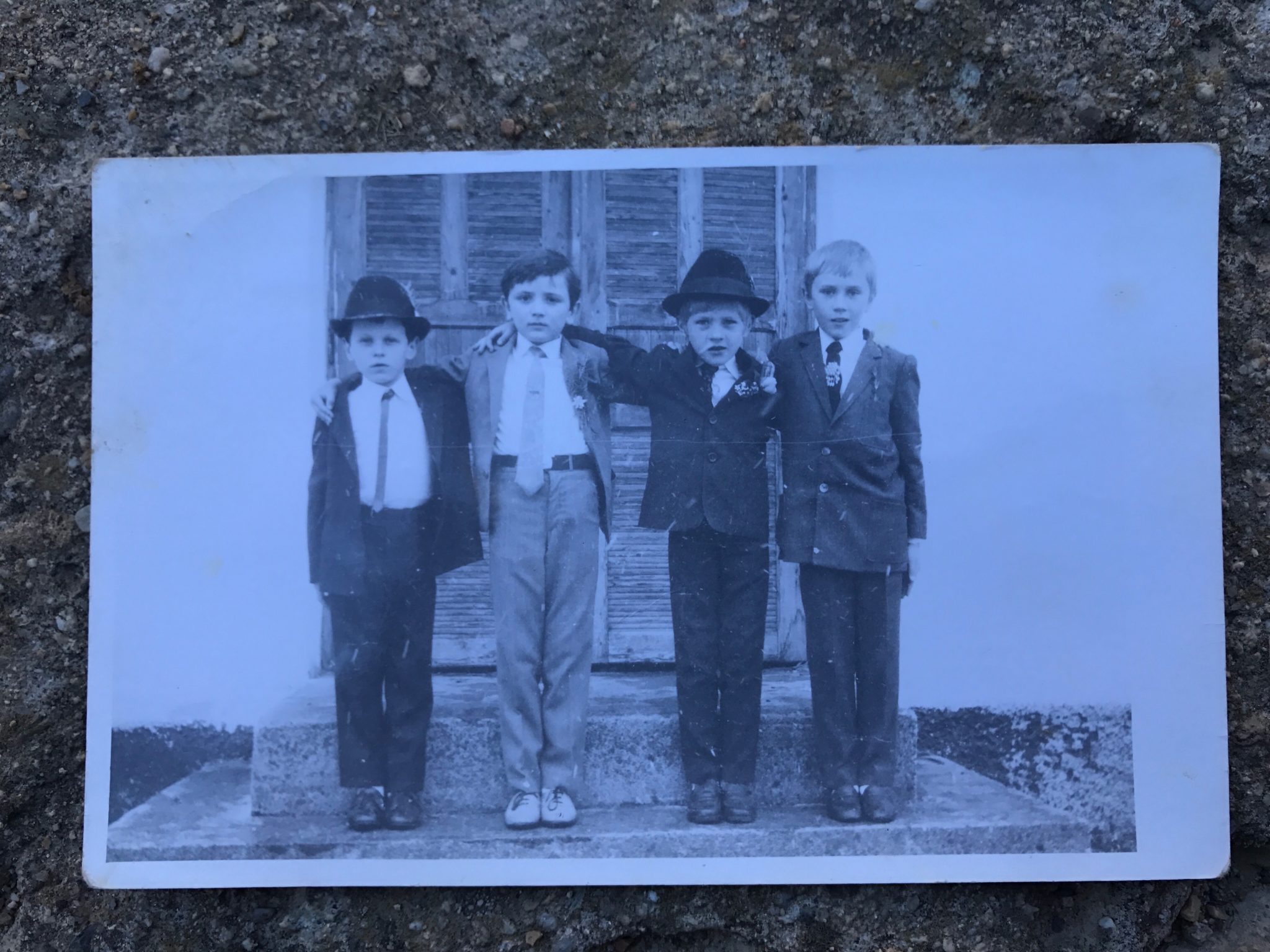

CHILDHOOD IN GÂRNIC

I was born in Romania, in Gârnic. My parents were both born in Gârnic. They were the fifth generation of Czechs in Romania. I am the sixth. I was born in ’85, a little before the Revolution. I remember the day Ceaușescu was shot. We had a black and white TV and there was only one TV channel, TVR1. I learned Czech from my parents and, at the age of three, I also started learning Romanian.

There was a doctor who used to come and speak to me in Romanian. There are a lot of us who, as children, don’t know Romanian. But I was three and I knew that “ant” is “furnică” in Romanian and “mravenec” in Czech. My grandmother scolded her.

– “This is going to drive him mad, he won’t know how to speak Czech anymore!”

In our village, school was in Czech until the end of fourth grade. Even mathematics was in Czech. After that we were taught in both languages.

Childhood in Gârnic was different from how it is now. We would all go to the fields, it would rain…

When I was little, they made me keep watch for snakes, I would stay in the wagon, I wouldn’t walk in the grass. I had to wait till they were finished, but you can imagine, I was impatient. When I grew up, I had to help around the house. My father passed away very early, at 39, he didn’t even get to turn 40. I learned to cut grass with a scythe from the age of 10 and to do other chores.

At the time, there were many children in the village. We used to build some bunkers in the forest, we called them koliba. In winter we had wooden skis. We skied in the garden, among trees, we made trampolines to jump on. We also fought each other. All the children on the street, we would meet at someone’s house, and we would make a trampoline. We’d be 10 boys and even some girls. The boys mostly used skis, the girls sledges.

FROM FLUTE TO SAXOPHONE

My father knew a little how to play the harmonica, my grandfather the flute, but I don’t know of any musical tradition in our family. But they knew a little how to play, both grandpa and dad.

I learned to play the flute when I was about 12. We had a Czech teacher, Pavel Sumec, who came from the Czech Republic to teach in Gârnic. When we were in sixth grade, he asked us who would like to learn to play the flute. Around 20 of us volunteered, he tested our musical ear by tapping on the table. Less than half of us passed, six of whom learned to play the flute after school. He taught us a few tunes, two or three, by notes.

The first time I played was at Sfânta Elena, I don’t know the exact year, but it is recorded in the library. I played two songs with Pavel. Him on guitar, me on flute. It was the children’s festival. After that festival, a neighbour who played the saxophone told me I should try the saxophone, that it wouldn’t be difficult to switch from flute. That boy lived across the street from the school, and he said to me:

– “Come to my place and try it!”

So after I finished school, I just crossed the street.

– “Blow, blow, it’s coming out nicely!” he would say to encourage me.

And so I learned a few songs. After that it was easy. Only blowing makes the difference between flute and saxophone.

Then I rented a saxophone. It belonged to the community, the community centre had instruments, and when I came home from the school in Moldova Nouă, I’d write down on the last page the tune I wanted to learn. On Saturdays, on weekends, I would learn the tune at home.

There has always been a band in Gârnic. Some of the musicians went to the Czech Republic, they knew about me and they invited me to play with them at a wedding in Sfânta Elena. That’s where I first played the flute on a stage. It was also my first time playing in a band at a wedding. It was a small wedding, not like the traditional ones that last three days. We only played for one evening. But I have also played at three-day weddings, mostly in Eibenthal. At baptisms or weddings where there were both Romanians and Czechs, we would play the Czech part, and others, from Timișoara or Caransebeș, would play the Romanian part.

Now I live in the Czech Republic, but people still play. Some of them are here and they meet. Or they take their holidays and go to Romania, or people come here.

POOLED SHEEP, COWS AND MILLS

When I was in school, on Saturdays we used to take the sheep grazing and we would take turns watching them. Each family sent their sheep, and the children took turns watching them for a certain number of days, depending on how many sheep the family had. I always used to play the flute when doing that. The lambs grazed separately. I even lost them at one point. Together with Václav, a friend of mine, we went to the cherry orchard looking for cherries. They were hard as rocks, they weren’t yet ripe. But before we knew it, it was evening, and the sheep were gone. We sat on a corner thinking the sheep would come to us. We knew their usual route and we waited for them to show up. They didn’t, but our parents did. They came looking for us.

– “Where are the lambs?”

– “We don’t know.”

They found them at the other end of the village.

The mills were also cared for by the community. They’re still there and still working, they’re over a hundred years old. There were about ten families taking care of a mill, ensuring its maintenance. It was the same as with the sheep. Everybody had a certain day when they were grinding. Now they don’t take turns anymore because it’s always free. There are still two or three people who use it, but it’s not crowded anymore. Before the Revolution there were 960 inhabitants in the village. Now there are 160, mostly old people. It’s not crowded anymore.

There were three more mills outside the village, my grandfather had his turn at the first mill. I was really glad when I saw that one of them was restored. But I only got to visit it, I didn’t get to try it out. The one where my grandpa used to grind is by the signpost indicating the direction to Sichevița, it’s the first one you see.

We also had to watch the cows when they were grazing because there were no electric fences. I saw the first electric fence in 1999 at the zoo in Plzeň.

LEAVING GÂRNIC

Immediately after the Revolution, people started to leave. I was young at the time. The first one to leave was a man born in Ravensca who had married a girl from our village. He used to work at the town hall, he was called Balat. He was among the first to leave. The next one I think was Špicel Alois, he was the school headmaster when I was little. His wife was my kindergarten teacher. I didn’t really like kindergarten. When my sisters were going with me, I liked it, but I didn’t want to go on my own.

A family left. Then another, then two more, who stays… Chaos.

Then the mine started to reduce its activity. The men were working at the mine in Moldova Nouă. After the Revolution, they had the opportunity to go to the Czech Republic. They knew the language, so they gave it a try. The first one tried, then two, then three, until… Some even had good jobs. There was a man who worked at the town hall. My grandmother said to him: “You’ve only just finished building your nest and you’re going to leave it?” It’s the last house on the left when you go to Sfânta Elena. He had just built it, it wasn’t even finished, and he left.

It took me a while to decide to leave. We were 12 friends and only one of us remained in the village. I was the 10th to leave.

We had work, but it wasn’t enough, and tourism stopped because of Covid, and we were kind of stranded. Before Covid, Maruška worked exclusively in tourism. Five hundred tourists from the Czech Republic passed through our courtyard every year, maybe more. In 2020, there were only eleven. Nine from the Czech Republic and two from Romania. I counted them. Eleven in 2020. In 2021 it got better, but the number was still low. Plus, there were other problems.

I went to the Czech Republic following in the steps of my wife’s parents. She has an older brother who also lives here, all her family came here a long time ago. It was a place to start from. Maruška and the children left first, I stayed on, I put our affairs in order. The children came first, then Maruška, then me. We made three separate trips. After she got here, Maruška made a list of things I should bring from home, it’s a long way to keep moving things.

I have two sisters. One is six years older than me, born in ’79, the other one nine years older than me, born in ’76. Both of them live in Moldova Nouă. They stayed there, relatively close to our mother.

ADAPTING TO THE CZECH REPUBLIC

The Czech Republic wasn’t a completely new place for me, I used to come here for a week every year. I had family here. But it wasn’t easy. The first month, a nephew sent us some money and one of the tourists who had stayed with us took me on a seasonal job, to make some money, to get us started. Tomáš. We were at his place for three days. He helped us a lot in the beginning.

As soon as we arrived, the children started school. It was autumn. The first two months were hard, even for us… But the headmaster was pretty welcoming, his daughter had been to Gârnic. So he knew that the children spoke the language well. He said:

– “I can take them for, let’s say, two months. They’ll be on probation. If they manage, we’ll let them continue. If they don’t, they’ll have to repeat the year so they can integrate.”

They managed.

We were busy with work. Here, I work every 12 hours. I work 4 days, the next 4 days I’m off. Back in Romania, I was working eight hours every day, Monday to Saturday. I only had Sundays off. Here I go to work, today is the fourth day in which I am working 12 hours, then I have four days off, so Saturday we can go somewhere with the whole family. Not long ago, we went to Karlovy Vary. I’ve also been on a bike ride with my children. To get them away from the computer, we went to pick cherries. We biked for 11 kilometres, we picked cherries and then a trailer came and picked us up, took us home. But we could have managed coming back on bike.

Luckily, we still have a house with a courtyard. The children wouldn’t have been able to get used to an apartment. We have garlic from Romania, we brought it. We’re preparing it the Gârnic way. And the garlic, also from Gârnic. There’s a big difference between Romanian garlic and Czech garlic. And when someone goes to Romania, we ask for pufuleți! When we arrived to the Czech Republic, we also brought pufuleți, because there aren’t any here. Or maybe they are, but not like the ones in Romania.

Anyway, we’ll always go back to Gârnic. My youngest, I went with him to Lidl and he said: “Look, it’s just like home”. Home will always be the nest in which you were born. I could almost cry when I heard him. “Look, it’s just like home.” Just last week I went to Lidl, and everything was set up just like in Moldova Nouă.

WE CAME BACK TO THE PLACE OUR ANCESTORS LEFT

My mother’s family comes from the Hromnice area, very close to where we live now. I went to find out if the Bouda family is really from that area. My father’s family came from a place 10 kilometres away from Tachov. They were called Kuska, there were few of them. It’s an industrial area. When I came here for seasonal work, on my way to the accommodation, I used to pass a signpost, Tachov. That’s where my father’s great-grandparents came from, as far as I know.

We returned to the area that our great-great-grandparents left 200 years ago. After six generations. My children are the seventh generation. No stories or legends of our family’s departure from the Czech Republic have survived, but my grandmother tells the story of how they left for America after World War I. I may have relatives there, but I don’t know. Someone wrote to me saying that his grandmother was also called Karolina Kuska, it’s possible that we were related generations go, so they looked us up.

In the Czech Republic we returned to our place of origin, but we still have Romanian citizenship, we don’t need another one. We are here legally, we work, our children go to school.

BACK IN THE CZECH REPUBLIC, WITH TRADITIONS PRESERVED FOR TWO CENTURIES IN THE ROMANIAN BANAT

We, the Czechs from Banat, still keep in touch in the Czech Republic, even though we live in different places. For example, on Saturday there is a is a wedding. The cermony is in Plzeň. The boy is from Gârnic. So is the bride. There are also meetings of the Czechs from Banat, here, in the Czech Republic.

I’ve been to one, there was a fășang at Všeradice… Masopust. The women wore traditional dresses. The Gârnic dress is the most complicated, the ones of other villages aren’t as complicated. It’s made up of I don’t know how many layers of skirts, maybe three, and it’s very complicated. Those who had their wedding in the summer, before the fașang – that’s like the first dance after the wedding – they are lifted to a special tune played for them. After that, their friends dance. We value our traditions here too.

But we still go to Romania on holidays. For Easter, for Christmas. This year is the first year I’ve been away. I was only there for Easter. Friday, Saturday, Sunday, then Monday I came back. I’ve been mostly on the road, almost. As I have been with the company less than a year, I don’t have the right to holiday yet. But we really need to go to Romania this summer, the grass needs mowing, I was thinking about it yesterday.

In the Czech Republic we are seen as Romanians, in Romania we are pemi. We are somewhere in between, both here and there. But here, many people know about the Czech villages in Banat. When Maruška went to the emergency room last week, the doctor asked her about the nationality.

– “I’m from Romania.”

– “Wow, and you speak Czech so well!”

– “Yes, I’m from Banat.”

– “I’ve been there!”

– “Who did you stay with?”

– “Mr. Mašek!”

The woman had been to our village. The links between the Czech Republic and Romania have always existed, and always will. We will live here the Gârnic way.

Photo credit: Petra Dobruská