All the things a deported child cannot forget

Photographs and documents from the archive of Petronela Tămaș

When remembering the voyage into the Bărăgan, Petronela Tămaș (72) feels the taste of rotten cherries. In the night the soldiers knocked on their door in Dudeștii Vechi and hurried them to get on the train cars meant for transporting cattle that were waiting for them in the train station, without telling them where they are being taken, her grandfather took – along with furniture and a tarp – a basket of cherries. It was cherry season and the Ronkov96 family had picked a lot of them in order to make compote.

It was hot in the cattle box, the train stopped in certain stations, the people yelled ”Give us water, we can’t take it anymore”, and part of the soldiers took mercy and let them get out to look for water. But the soldier guarding them was scared and wouldn’t let them exit. Petronela was four, always crying and her parents were trying to calm her down: ”Shush, stop crying, go eat cherries.” But the voyage seemed unending and the cherries had gone rotten and she had to eat cherries in order to keep the thirst at bay. ”Two years ago I told my husband: <<I feel the taste of rotten cherries in my mouth, like the time they took us into the Bărăgan. I can’t stand it anymore.>>”

The deportation into the Bărăgan in June 1951 targeted the border area with Yugoslavia, where Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej feared that the leader in Belgrade, Iosib Broz Tito, could foment political dissent. The individuals targeted included foreign citizens, refugees from Bessarabia, former clerks and military personnel that had been purged, former big landowners and former political prisoners. In total, over 40,000 people fell victim to the operation.

Petronela Tămaș is rummaging through papers and old photos, finding the paper that brought with it the deportation of her family and starts reading:”In order to ensure the security of the border area with Yugoslavia, some categories of dangerous or potentially dangerous elements shall be displaced on a stretch of 25 km.” A paper had arrived from Bucharest having on it the number of families to be deported from Dudeștii Vechi, an ancient Bulgarian community in the Banat, but the local party secretary and the mayor were the ones writing up the lists of names. In writing the list, not only the number of hectares owned, ethnicity or political status mattered, but also local rivalries.

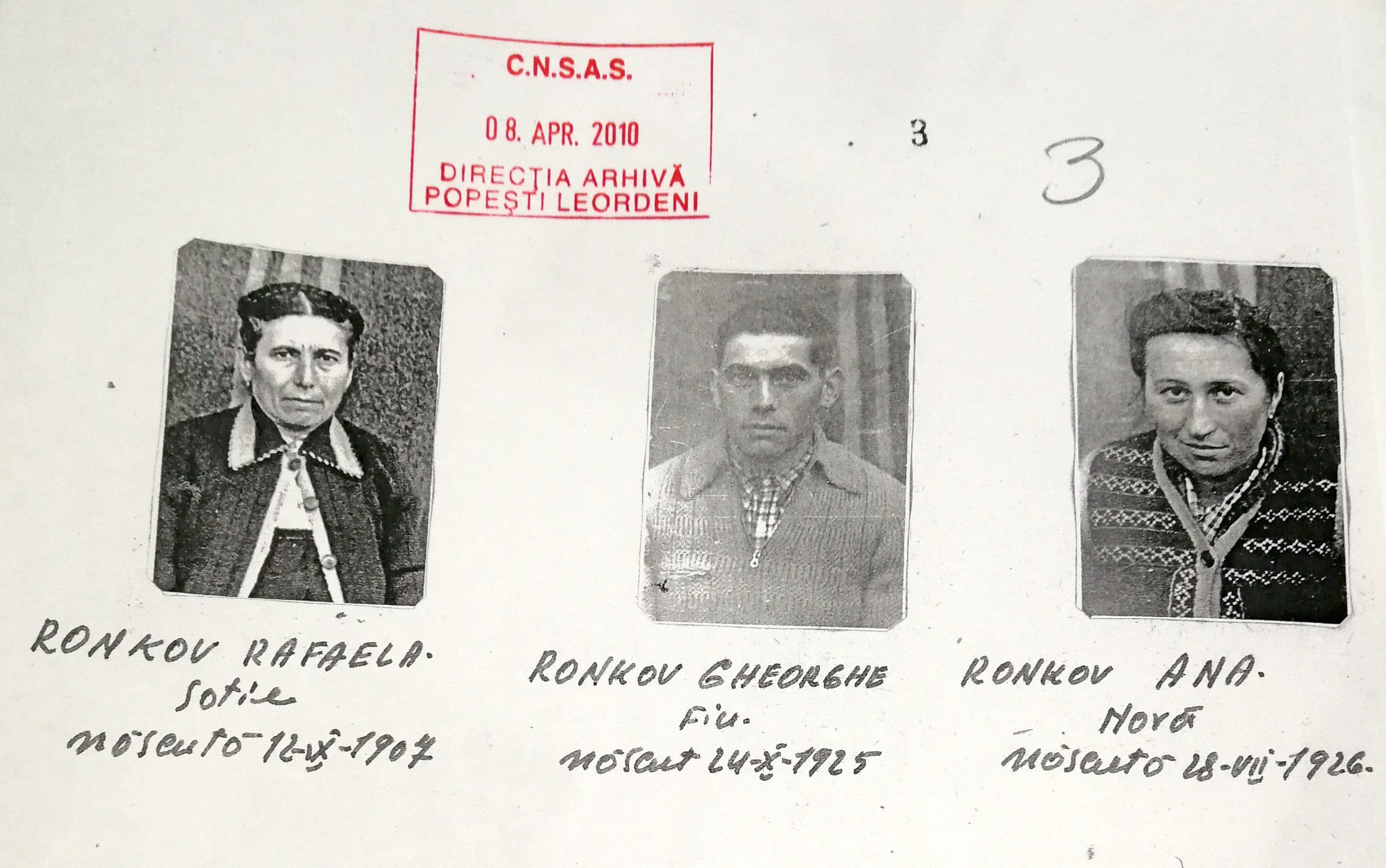

Petronela’s parents and grandparents were deemed ”dangerous elements” because they owned 37 hectares of land and because her grandfather had been a member of the National Liberal Party – the Brătianu wing. They were first on the list because the local party secretary wanted to take revenge on Petronela’s mother, Ana Ronkov, after an incident where the woman had made him lose face in public. A month before deportation, the Communist grandee had come with gendarmes looking for Ana’s brother, wanting to kick the door in. Ana, 8 months pregnant at the time, tried to stop them, shoving the secretary down the stairs and beating him. They then arrested her husband, Gheorghe Ronkov, putting him in a basement with wet sand on the floor and beating him to a pulp. ”And when they made the lists for the Bărăgan, the party secretary said <<you can change the rest of the names, but they stay on the 1st position on this list.>>”

***

On the Sunday of departure, the village drummer came in front of the church, beat on the drum and announced that ”in the coming five days, no one shall work the field, because the Army is holding live fire drills.” Meanwhile, train cars used for hauling goods were being pulled into the train station without no one knowing why. Following this episode, on the night between the 17th and the 18th of June, soldiers knocking on doors. 87 families were to be loaded onto trains.

From the night of departure, Petronela Tămaș remembers some knocks and adults talking: ”Come on dear, get up!” She didn’t understand what was going on, but she could see her parents crying. They loaded everything they thought they would need. They had new and beautiful furniture, made of walnut. Her grandfather, ”the practical type”, told them to bring the table along and her mother and grandmother ganged up on him: ”What do you mean take this beautiful table with us?” He told them: ”Are you both daft? Who knows where they are taking us and what we’ll do there? We need a table to sit on.” They took the table and that was what remained of the furniture because all the rest disappeared as soon as they left the house.97 Soon after their departure, the house and yard was emptied, the geese, pigs and everything else evaporating. A neighbor, his father’s friend, managed to keep a chandelier from the middle room that the thieves couldn’t detach from the ceiling. ”I kept this and that’s the only thing I could save.”

The road towards the Bărăgan lasted for three days. All of a sudden, the door of the cattle box opened to let in cool air and the train stopped and one of the horses got scared and jumped off the train. The grandfather jumped out after the horse out of reflex and the train started again. At the first train station stop, Petronela’s father asked the ones guarding them to let him go back along the train track to find him. The grandmother, the pregnant mother, a 16 year old aunt and a 4 year old girl stayed behind, continuing the journey on their own. Until they got off, they were the last to arrive. When they arrived to the place designated for the deportees, the settlement which was to be called Valea Viilor, they found land plots marked with 4 stakes in the earth. There was only one plot left, close to the edge, where they would start building their shelter. Some time afterwards, the father and grandfather returned.

They erected a sort of tent with the tarp taken by the grandfather from Dudești. ”And we stayed there. Others had less than that. The others, when the rains came, stuck their kids in the closet. There was nowhere else.” They had also brought along a cooktop: they fixed on top a mound, fired those kind of thistles that were rolling around everywhere together with corn roots underneath, and that’s how they cooked their food. They let other women cook soup for their children, the need for survival bringing them closer.

In the beginning, the locals were scared of them, mostly because of the rumors being spread by the authorities and they didn’t even want to let them draw water. They went to a well dug inside a state farm but all of a sudden they found the place surrounded by barbed wire and couldn’t take any more water from there. ”By the end of summer, beginning of autumn, a lot had died because they drank dirty water from Borcea [canal].” When they saw a cloud and thought it was about to rain, they took out all their pots and pans, including plates and tea cups and waited for water from above. The thirst was torture. Petronela remembers going out on the road and seeing a hoofmark filled with water, wanting to drink the water gathered there and another girl came along and they started fighting: who should drink first?

A girl that was the same age as she got sick and her parents took her to a doctor that had also been deported. The doctor told them that he knows what disease the girl is suffering from, but that he doesn’t have any medicine, so he told them to try a hospital in Constanţa. A teacher taught them to write an application. The answer took a while getting back: they found out they could take the girl to the hospital on the day she died. Another child in the deportees’ village lived because his parents risked it and took him straight to the hospital, where a good-hearted doctor gave them the medicine they needed without anyone seeing.

Petronela’s sister was born in the Bărăgan, less than two months after the family’s arrival. Her mother gave birth in Fetești. One day after giving birth she was told that she was no longer allowed to stay in the hospital, sending her back to the 4 stakes in the ground together with the baby. ”There was unbearable heat, cold, the wind blew and we stayed in the tent and grandfather said: <<We can’t keep going on like this. We need to do something.>> He dug a hole and made a shanty. But not like shanties from old times, it was more like being buried alive. Only two beds fit inside: grandfather slept with grandmother, father and mother and me slept in the other bed and my little sister was sleeping in her cradle. And one night there was such a huge downpour that mother stretched out her hand to see how the baby was doing and noticed we were floating, cradle and all.”

In autumn they were distributed some building materials, in order for them to build houses. There were two types of houses, one with more rooms and one with just a room and a kitchen. They chose the second type because they hoped they would soon be returning to Dudești. The grandparents slept in the kitchen while the rest of the family used the room. The father found a job in Fetești, hauling bread with a wagon from the local bakery and when he could bring a loaf home, he shared it with other unfortunate deportees. The grandfather found work where he could. At one time he helped someone slaughter a bull. They didn’t pay him for the work but said: ”Look old man, take the bull’s head, bring it home.” The man took the head, put it on his shoulder and went home. He arrived covered in blood and grandmother got scared and started trembling: ”My God! What did they do to you? They killed you!” To which he replied: ”Shut up, there’s meat to be had!”. ”And not even that meat, the amount we had, he never referred to it in the manner of: <<This is ours only, we’ll eat of it for three days.>> He invited my aunt, who had married in the meantime, and gave her a piece”, Petronela Tămaș remembers.

Her and her sister walked barefoot until the thistles punctured their feet and the wounds started running with pus. When he noticed, the grandfather took a piece of wood, sculpted it with his axe and made clogs, which were held to the feet using oil lamp fuses. ”We walked around like this, me and my sister, God! We were so happy nothing was stinging us anymore! And then he found thicker fuses – and when he fit those on the clogs – the first year we used them to walk in winter as well. We didn’t have anything else.”

Before the first winter in the Bărăgan, the relatives from Dudești put some money together in order to send them a train car full of clothing and food. The relatives managed to recover the father’s winter overcoat and some other things. They packed ham, flour, everybody pitched in any way they could. Right before leaving, the man who wanted to brave the road, remembered to take some mint for the little girls and put it in his coat. When he reached Fetești, the authorities were waiting for him. They told him he was not allowed to take anything with him and confiscated the goods, threatening him that he would be jailed. But, after confiscating everything, they let him go and the man managed to get to where they lived. He only brought the mint he had forgotten in his jacket, to be used for tea, ”that’s the only thing they didn’t take.” The father that was hauling bread in the city came back sad one evening and told the mother: ”I’ve seen my winter overcoat.” Someone was wearing it on the street but he couldn’t confront the person. The authorities had sold the confiscated goods to the locals and the stranger probably didn’t know that what he bought was confiscated property: he was just happy to get a winter coat.

She remembers a horrible winter. Their house was at the edge of the settlement and was windswept from all sides, the snow getting so big that it covered their house. They couldn’t see anything and couldn’t close the door because it opened by pushing out. They were stuck inside. They had luck with an old man that remembered where the house was, buried under all that snow, and gathered all the people who could get out of their houses in order to dig them out. ”I can still hear my grandfather telling me and my sister: <<Yell louder!>> And they dug us out, but I remember they did if from above. Even now when I close my eyes and see a grey darkness, I remember those images.” They had been buried for over a day.

After a while, the locals started understanding the deportees’ situation, catching on that they were not guilty of breaking the law. They figured they had what to learn from the deportees. From the Bulgarians, for example, who were skilled gardeners, they learned how to tend vegetable gardens. In exchange the locals helped them communicate with the outside world. The deportees were not allowed to send letters to Dudești, only postcards on which every word could be seen. Her father found someone in Fetești who could receive letters from Dudești instead of them, and that person brought them news from home. The village was in a far away place, a sort of lost paradise.

***

Petronela Tămaș is holding a picture taken in the Bărăgan, in the first year of they arrival. To her left is her father with a big sheep wool hat on his head. Next to him is her mother holding the baby. Petronela is to their right with her hand hanging by her body. If you wouldn’t know the suffering gathered into those moments, you would think it an ordinary family picture.

In December 1955 the restrictions started to lift and on the 28th of January 1956 they left for Dudeștii Vechi. But their former life was not waiting for them to return: part of their house was now occupied by an officer together with his wife, and the other part of the Ronkov house had become an Army slaughterhouse. The room that was at the street was used by the butchers to clean entrails: they had dug a hole in the wall and were throwing buckets full of muck through the hole directly onto the road. They lived with a neighbor for a while, wrote countless and useless applications to the town hall, until one of the butchers working in their house taught them how to proceed: just move into a room that had been turned into a chicken coop and confront the new tenants with a fait accompli. It turned out that nobody turned them away, but it wasn’t comfortable either.

They still felt the hate that had taken over the village as Communism set in. Each family was being followed and they never talked about their experiences in the Bărăgan. ”Grandfather said:<<If they ask, tell them nothing because we might get into worse trouble>>. And we all had this dear. And even as the years passed by I kept silent. An animal’s type of fear had entered us and wouldn’t let go.”

The children of former kulaks were not allowed to attend highschool. Petronela started school in the Bărăgan at six, being a good student. After graduating from the gymnasium she continued going to school in Sânnicolau Mare, but when she got to the administrative office they asked her how dare she take up one of the places reserved for the working class, and therefore would not accept her.

Her mother thought it would be best she attended a vocational school, but her father stuck to his guns meaning for his girl to go to highschool. They found out a new highschool had opened in Nădlac and they sent her there in secret, in a wagon. The Communist big-wigs in Dudeștii Vechi found out and try to sabotage the affair but did not succeed. Petronela graduated highschool in 1964 and took the exam for getting into the Literature Faculty in Timișoara, being admitted. She had left out of the admission form that she was the daughter of a kulak. When it came out there was a huge scandal and they summoned her in front of a commission but she managed to get out of it because one of her father’s colleagues was the chief accountant of the faculty, managing to pull some bureaucratic and financial tricks. Her father was working hard for her to finish her studies: ”While I was in highschool and college, he was a day worker. Working the vineyards with the pesticide pump on his back. An old lady told me: <<My god your father loved you so much, he used to cry and say: Even if I have to eat dust, my daughter will go to school.>>”

While being a student in college she met her actual husband, Cornel, who was training to become an agricultural engineer. They settled together in Dudeștii Vechi. He worked in his area of expertise and she became a teacher. They started a new life but the Bărăgan always lingered in her memory.

***

Petronela Tămaș doesn’t understand why the history of deportation should be washed away clean, the way the authorities have tried countless times. As soon as she could, she started asking for archive documents and advised others to do the same. She would like the world to understand what it was like so that it should never happen again.

The deportee settlements have been razed and few of those still left there today still remember something about it. ”And it will all wash away, as I am 72 and back then I was only 4. Who’s still alive? Nobody. The ones that were there and suffered have forgotten. When I was younger I didn’t have so many questions, but now I’m sorry I didn’t ask father more about it. He didn’t say much. Until grandfather died he never wanted to talk about it.”

Luca Ronkov died in 1982 and never got to see his land back into the family’s possession. He died hoping that it would happen at some point. When they tried turning the grain shed into a bathroom, grandfather wouldn’t let them because he was thinking that times always change and should they recover their land, they would be needing a good storage space.

Shortly after 1990 they recovered their land, but didn’t have the tools needed to work it and the state wasn’t going to help the peasants. When an Italian company showed up in Dudeștii Vechi offering to buy up land, the people starting selling it for a pittance. ”basically forced us into it. I initially said: <<Cornel, I’m not selling a hectare of the land where my parents were sent into the Bărăgan and suffered so much for.>>” She didn’t have the property records yet and the mayor threatened that if they didn’t sell the land to the Italian, then she would get some bad land next to some big puddles, unworkable land. ”So what were we to do? We sold it.” They kept the land the Italian was not interested in and they still work it in any way they can, raising animals.

The community in Dudeștii Vechi is coming apart, and it all started, when the trains were waiting for them at the station. ”They changed the lives of people forever. This has haunted me. I am thinking of the parents, because I am one now as well. I am thinking how difficult it must have been. Me, being a child, didn’t quite understand it. But as a parent, with your child crying of hunger and you having no food or wanting to go to school and being unable to…”. She fights with her sister sometimes who claims ”the Bărăgan wasn’t that bad.” But her sister was too small to know. But Petronela remembers everything: how the house there used to look, what the street was like, how grandfather had planted a wax cherry tree and she believes that it would bear fruit instantly, and him telling her that see, now we have fruit trees it will turn out well.

This story was initially published in the MOVING FIREPLACES. 2019 book.

Leave a Reply